The Benefits of Remedial Massage

We all crave the occasional indulgence. A mindless distraction or a little treat to reward our hard work…

Some people see massage as an indulgence, but the good news is that unlike many of the indulgences we crave, massage has several reported health benefits. Moreover, as health and wellness interventions go, massage appears to be a great deal! But as always, we delve a little deeper to what the evidence shows.

Massage has always, and remains to be, a popular treatment choice for athletes, coaches, and sports physical therapists. However, with several purported benefits delivered through numerous psychophysiological mechanisms, the evidence with regard to the effects massage is limited and equivocal (Arroyo-Morales et al 2011).

The practice of massage therapy involves kneading or manipulating a person’s muscles and other soft-tissue. It is a form of manual therapy that includes holding, moving, and applying pressure to the muscles, tendons, ligaments and fascia. The premise of how the mechanical pressure from the therapist during a massage can affect the patient is summarised into four proposed mechanisms (Weerapong et al 2005):

Biomechanical

The mechanical pressure may Increase muscle compliance resulting in increased range of joint motion, decreased passive stiffness and decreased active stiffness (Hopper et al 2004). Mechanical pressure also can increase blood flow by increasing the arteriolar pressure, as well as resulting in a higher muscle temperature from the effects of the rubbing.

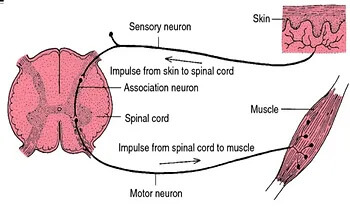

Hoffman Reflex – how affecting the skin can affect the muscle via neural excitability

Neurological

Depending on the massage technique, mechanical pressure on the muscle is expected to increase or decrease neural excitability as measured by the Hoffman reflex. A study looking at massage on the calf (Morelli et al 1990) suggested the use of massage as an alternative to other therapeutic modalities such as passive muscle stretching and tendon pressure to decrease spinal motoneuron excitability (i.e increase muscle relaxation).

Physiological

Changes in parasympathetic activity (as measured by heart rate, blood pressure and heart rate variability) and hormonal levels (as measured by cortisol levels) following massage result in a relaxation response.

Psychological

A reduction in anxiety and an improvement in mood state also cause relaxation, and has been shown prior to sports to help lower performance anxiety.

Ultimately, what the above proposed mechanisms translate into a series of studied benefits on specific conditions. According to the Massage and Myotherapy Australia website, massage has also been shown to help:

- Back pain

- Arthritis

- Insomnia

- Headaches

- Depression and anxiety

- Constipation

- High blood pressure

- Chronic pain

All in all, massage provides good bang for buck when used in the appropriate setting. Our mantra at Praxis is Prevent Prepare Perform and as physiotherapists, we work in tandem with our qualified massage therapists to deliver the best results for a wide variety of conditions. Whilst, physiotherapy is focussed on the diagnosis and treatment of acute or chronic injuries, remedial massage enables a little more hands on time to truly address issues that our physiotherapists may have identified in their sessions. Further, massages offers a great medium for regular ‘tune-ups’ when the rigours of training and working take their toll.

We ensure that your massage experience is not only blissful, but productive for your rehabilitation as well. So if you have been swayed by the evidence, or just looking for that little reward, we are here to help!

Until next time – Prevent. Prepare. Perform

References:

- Hopper D, Deacon S, Das S, et al. Dynamic soft tissue mobilization increases hamstring flexibility in healthy male subjects. Br J Sports Med. 2004;39:594–598

- Weerapong, P., Hume, P.A. & Kolt, G.S. The mechanisms of massage and effects on performance, muscle recovery and injury prevention. Sports Med 2005; 35: 235

- Morelli M, Seaborne DE, Sullivan SJ. Changes in h-reflex amplitude during massage of triceps surae in healthy subjects.J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1990;12(2):55-9.

- Arroyo-Morales M1, Fernández-Lao C, Ariza-García A, Toro-Velasco C, Winters M, Díaz-Rodríguez L, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Huijbregts P, Fernández-De-las-Peñas C. Psychophysiological effects of preperformance massage before isokinetic exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Feb;25(2):481-8.

https://www.massagemyotherapy.com.au/Home