FACT OR FICTION: Is running bad for your knees

We at Praxis think that patient education is the cornerstone of good physiotherapy. We particularly enjoy discussing people’s understanding of their injuries or the beliefs around certain activities. As such we are starting “Fact or Fiction Friday’s” in which we tackle some misconceptions that may negatively affect people’s rehab or willingness to participate. To get us off and running (love a pun) let’s start with:

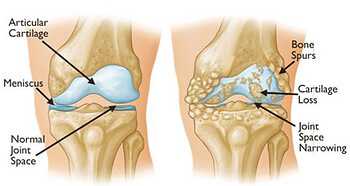

QUESTION: Recreational running will wear out your knees (quicker than not running)

ANSWER: FICTION

Running appears not to increase risk of osteoarthritis in knees unless you are a competitive long distance runner. Even then, you are only slightly above the average for non-runners but enjoy the myriad of other benefits that exercise brings.

Check out our previous post on this here. If you are a runner or have knee pain, book in with us so we can assess you and get you back to what you love doing. Call (07) 3102 3337 or book online

#running #arthritis #osteoarthritis #kneereplacement #preventprepareperform #kneepain #sportsinjuries #runninginjury #knee #praxisphysio #kneephysio #kneearthritis #endurancerunning