ACL Rehabilitation: The Role of Physiotherapy in Returning to Life, Activity, and Sport

On today’s Praxis what you Preach, we cover a very common injury here in Australia – the Anterior Cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. At Praxis Physiotherapy, we understand that recovering from ACL reconstruction is more than just healing a knee — it’s about restoring confidence, movement, and returning to the activities and lifestyle that matter most to each person. Physiotherapists are uniquely placed to guide this journey from surgery through to return to everyday function, recreation, and sport.

What is an ACL Rupture?

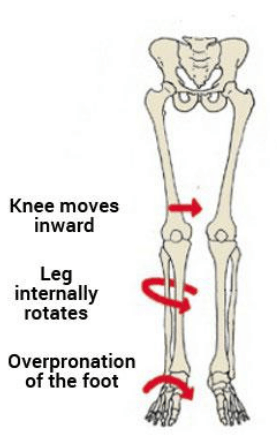

The ACL is one of the key stabilising ligaments of the knee, crucial for controlling rotation and forward movement of the tibia. An ACL rupture typically occurs during sudden changes in direction, pivoting, or awkward landings — common in sports like AFL, soccer, basketball, and netball. It most often affects young, active individuals, particularly females, due to biomechanical and hormonal factors. While not all ACL injuries require surgery, those with complete ruptures who wish to return to cutting or pivoting sports usually undergo ACL reconstruction. Regardless of the surgical decision, structured rehabilitation guided by a physiotherapist is essential for a successful recovery and long-term knee health.

The Importance of Physiotherapy in ACL Rehab

Research shows that while around 80% of individuals return to some form of sport after ACL reconstruction, only 65% return to their preinjury level and just 55% to competitive levels (Andrade et al. 2020). Physiotherapy plays a vital role in improving these outcomes by guiding progressive rehabilitation and using structured criteria-based progressions.

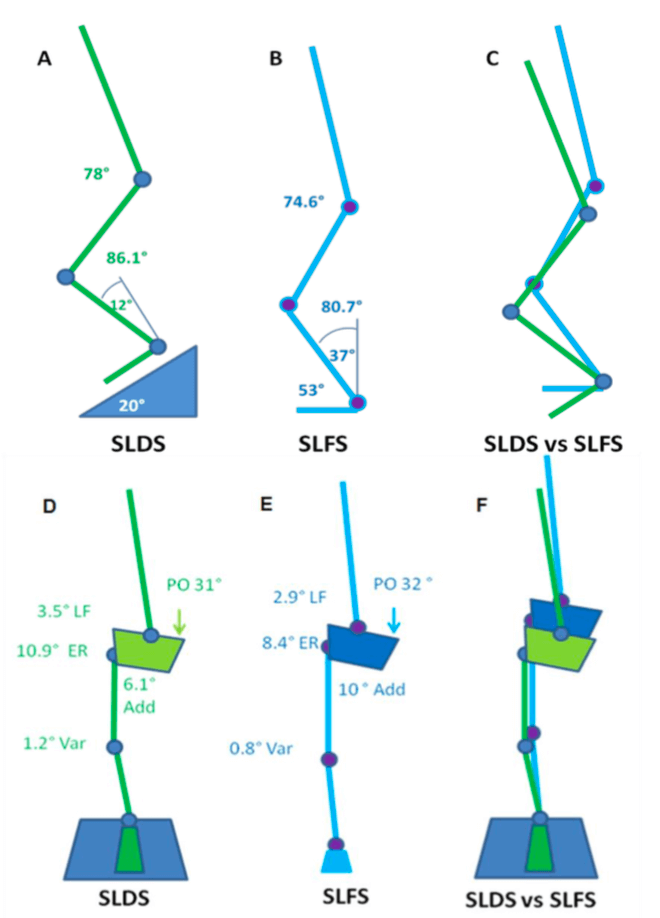

Physiotherapy-led rehabilitation should begin early, with emphasis on knee mobilisation, weight-bearing as tolerated, and initiation of neuromuscular training (Andrade et al. 2020). The BJSM systematic review of clinical guidelines for ACL rehab supports early kinetic chain exercises (both open and closed), strength training, cryotherapy, and neuromuscular stimulation when indicated (Andrade et al. 2020).

From Healing to Performance: A Continuum

Recovery after ACL surgery should follow a continuum from impairment-based care to performance restoration. This includes early pain and swelling control, progressive strength and range of motion restoration, motor control retraining, and sport-specific preparation. At Praxis, we follow a phase-based rehabilitation model tailored to individual needs. These needs may include the type of surgical graft used, concurrent injury (e.g meniscus / MCL), the operating surgeon’s post-op protocols, the patient’s goals, sport-specific demands, timelines for return to competition, and previous levels of function — all of which require thoughtful and collaborative clinical decision-making.

Unfortunately, studies show that many patients are discharged before meeting strength or performance benchmarks — particularly in strength-focused exercises like the split squat, squat, or deadlift, which play a vital role in ACL rehab progression. For example, performing around 22 single-leg sit-to-stands is one such late-stage benchmark that reflects adequate quadriceps strength and control before return to sport (Welling et al 2018). Nichols et al. (2021) found that most published rehabilitation protocols emphasize endurance and hypertrophy without progressing to the strength or power needed to reduce reinjury risk. This underlines the need for physiotherapists to include high-intensity, sports specific strength training and late-stage performance metrics as patients near return to sport.

Addressing Muscle Atrophy and Weakness

Quadriceps atrophy remains a key barrier to recovery post-ACL reconstruction. Evidence supports adjunct interventions such as neuromuscular electrical stimulation and blood flow restriction (BFR) training to combat muscle loss, particularly in the early post-operative period (Charles et al. 2020). BFR combined with low-load resistance exercise has been shown to reduce muscle wasting and promote strength gains when higher loads are contraindicated — we explore this more in our Blood Flow Restriction Training blog. We use this frequently at Praxis Physiotherapy in both reformer pilates and early gym based settings.

The Role of the Physio: More Than Just Exercise

Our job as physiotherapists goes beyond prescribing exercises. We support patients through the emotional and motivational challenges of recovery, address fear of re-injury, and help them develop the confidence to return to sport or physically demanding jobs. We tailor plans based on functional goals, sport-specific needs, and personal circumstances.

At Praxis, this also means working closely with coaches, GPs, surgeons, and families to ensure clear communication and aligned expectations. For sporting patients, this might include on-field rehab or comprehensive return-to-play assessments in collaboration with clubs and teams.

A Collaborative, High-Performance Rehabilitation Environment

At Praxis Physiotherapy, we bring high-performance rehab principles to all patients — not just elite athletes. Our team has provided physiotherapy services to the Aspley Hornets AFL Club since 2014, giving us deep insight into the physical and mental demands of competitive sport. We apply this same standard of care to everyday athletes, weekend warriors, and anyone seeking to return to an active lifestyle.

We also work closely with orthopaedic knee and shoulder surgeon Dr. Kelly Macgroarty, including in-room triage consulting, ensuring a seamlessly integrated, evidence-informed rehabilitation pathway. This collaboration allows us to align surgical timelines, post-op considerations, and physiotherapy progressions — from day one to return to sport.

Our clinical culture is shaped by exposure to elite-level sports environments, including AFL, representative athletics, and professional national cricket programs. But rather than highlight individual accolades, we’re most proud of the high clinical standards and systems-based approach that ensure our entire team delivers the same quality of care — no matter who walks through the door.

Each of our Brisbane based clinics includes access to gym facilities and reformer Pilates equipment, allowing for real-world, function-driven exercise. These resources support patients to not only recover structurally but also return to high levels of strength, coordination, and performance in line with the latest evidence-based guidelines.

A Message to Our Patients

Whether you’re an athlete aiming for competitive return or someone wanting to run after your kids again, we bring the same level of care and attention to your ACL rehab. Recovery is not just about timelines — it’s about building back strength, movement, and trust in your knee. Ready to get started with your own recovery plan? Explore the ACL physiotherapy services at Praxis and book an appointment today.

Until next time, Praxis What You Preach…

📍 Clinics in Teneriffe, Buranda, and Carseldine

💪 Trusted by athletes. Backed by evidence. Here for everyone.

For more insights into long-term knee health, including non-surgical rehab, check out our Knee Osteoarthritis blog.

References

Andrade R, et al. (2020). How should clinicians rehabilitate patients after ACL reconstruction? A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Br J Sports Med, 54(9), 512–519.

Kochman M, et al. (2022). ACL Reconstruction: Which Additional Physiotherapy Interventions Improve Early-Stage Rehabilitation? Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(23), 15893.

Charles D, et al. (2020). A systematic review of the effects of blood flow restriction training on quadriceps muscle atrophy and circumference post ACL reconstruction. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 15(6), 882–889.

Nichols ZW, et al. (2021). Is resistance training intensity adequately prescribed to meet the demands of returning to sport following ACL repair? A systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med, 7(1), e001144.

Welling W, Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, Otten E, & Seil R. (2018). Low rates of patients meeting return to sport criteria 9 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective longitudinal study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 26(12), 3636–3644.