Hamstring Strain Injuries: Lessons from Personal Experience and the Latest Research

Recently, in an effort to keep the ballooning effects of the all-you-can-eat buffet at bay during my Cricket Australia Indian tour, I ramped up my high-intensity running load. Things were going splendidly — four days of high-intensity running under my belt — until day five, when 90% of the way through a very intense interval session, I tore my hamstring.

I felt the tell-tale sensation so many of my patients describe: a sharp tearing and retraction sensation in my outer thigh while sprinting. I had to pull up immediately and iced the injury straight away. You’ll be happy to hear that I’ve since fully recovered. No longer ‘gun shy’ at my top speeds (which, admittedly, are not that fast!), my strength has vastly improved, and I’m back running at full capacity.

Having treated countless hamstring injuries through my long involvement in recreational, semi-elite, and elite sport — especially with Cricket Australia teams and the Aspley Hornets NEAFL squad — this experience gave me even deeper appreciation for how tricky these injuries can be. Hamstring strains are one of the most common injuries in running athletes, responsible for significant downtime and lost performance. Hamstring injuries have remained the most prevalent injury in professional AFL for the past 21 consecutive seasons (Orchard et al., 2013), with the average 2012 injury costing clubs over $40,000 per player!

Understanding Hamstring Injury Mechanisms

Most hamstring tears occur during the late-swing phase of running, where the hamstring undergoes rapid lengthening while producing high forces (Danielsson et al., 2020). Key risk factors include:

High eccentric loading demands.

Poor neuromuscular control.

Muscle imbalances (particularly hamstrings vs quadriceps).

Fatigue — as evidenced by my own injury, occurring late in a demanding session!

Importantly, the long head of biceps femoris is the most commonly injured muscle, partly due to its higher proportion of fast-twitch fibers and its anatomical position under stretch during running (Martin et al., 2022).

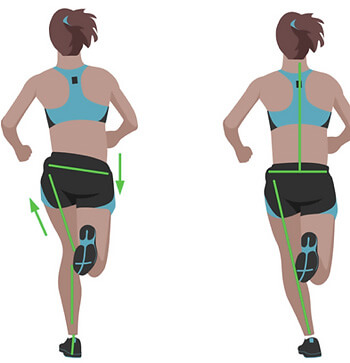

Fatigue, poor trunk/pelvic control, and sudden spikes in high-speed running are emerging as significant contributors to hamstring strain risk, particularly in field and court sports (Martin et al., 2022).

Preventing Hamstring Injuries

The good news is, hamstring injuries can often be prevented with smart training. Strengthening the hamstrings through eccentric exercises like Nordic hamstring curls and single-leg Romanian deadlifts has been shown to reduce injury rates significantly (Al Attar et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2022).

Effective prevention programs should also include:

Agility and trunk stabilization exercises — not just strength work (Martin et al., 2022).

Warm-up routines with dynamic stretching and sport-specific drills.

Monitoring high-speed running loads to avoid sudden spikes in intensity.

Addressing muscle imbalances is key too. Maintaining a healthy strength ratio between the quadriceps and hamstrings — and ensuring good trunk and gluteal control — promotes optimal biomechanics and reduces injury risk (Martin et al., 2022).

Recovering Well After a Hamstring Injury

A proper recovery should include:

Early management: Controlling swelling and pain with ice and appropriate activity modification.

Progressive eccentric strengthening: Integrated carefully to build resilience.

Functional rehabilitation: Sprinting drills, agility work, and sport-specific movements are crucial before returning to full play (Martin et al., 2022).

Interestingly, studies show athletes who follow programs that include eccentric training and trunk stability work have lower reinjury rates than those who just focus on basic strength and stretching (de Visser et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2022).

Return-to-play decisions should be made carefully. Factors like strength symmetry, absence of pain, and readiness for high-speed running should all be considered to reduce the risk of reinjury, which can be as high as 30% otherwise (Martin et al., 2022).

Final Thoughts

Even as a physio, my personal hamstring tear was a stark reminder that fatigue, progressive loading, and structured rehab are vital ingredients for both prevention and recovery. Whether you’re a weekend warrior, a professional cricketer, or just trying to beat the buffet, hamstring health is crucial.

If you’d like help strengthening your hamstrings, managing an existing injury, or optimising your running and performance, feel free to reach out. I (and my hamstrings) would be happy to help!

Till next time, Praxis what you Preach!

Backed by evidence. Trusted by athletes. Here for every body.

References

Al Attar, W.S.A., et al. (2017). The effectiveness of injury prevention programs in reducing the incidence of hamstring injuries in soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Physiotherapy, 63(1), 11–17.

Danielsson, B., et al. (2020). Mechanisms of hamstring strain injury: current concepts. Sports Medicine, 50(4), 669–682.

Martin, R.L., et al. (2022). Hamstring strain injury in athletes: Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 52(3), CPG1–CPG44.

Orchard, J.W., et al. (2013). AFL Injury Report 2012.