Your Guide to Total Knee Replacement Surgery

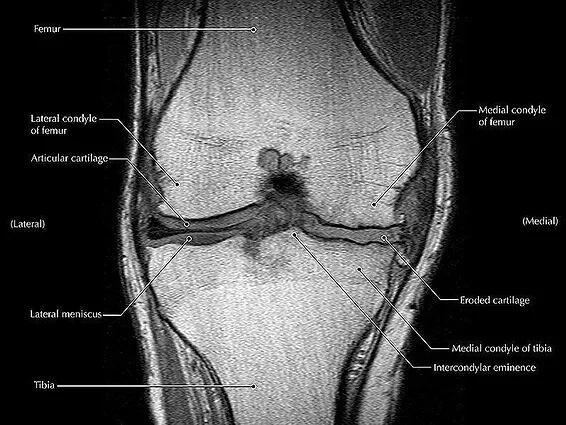

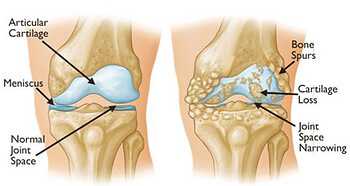

Total knee replacement (TKR) is a life-changing procedure for individuals suffering from chronic knee pain, typically caused by osteoarthritis. At Praxis Physiotherapy, we understand that total knee replacement (TKR) surgery is a major decision. As such, we are committed to helping patients navigate their surgical journey and maximize outcomes through tailored prehabilitation and rehabilitation programs.

This guide is designed to walk you through what to expect before and after surgery, how physiotherapy plays a crucial role, and the advanced, evidence-based services we offer to support your journey.

Why Physiotherapy Matters

Physiotherapy isn’t just something you do after surgery—it’s a vital part of your preparation. Prehabilitation (prehab) that begins around six weeks before surgery can improve muscle strength, mobility, and balance, leading to quicker, more successful recoveries post-surgery (Domínguez-Navarro et al., 2020).

Similarly, post-operative physiotherapy supports improved pain relief, better joint function, and faster return to daily activities (Artz et al., 2015), (Fatoye et al., 2021).

Pre-Surgery: Building a Strong Foundation

It’s easy to think, “Why do physio now when the knee is being replaced anyway?” But strengthening and conditioning your body beforehand significantly boosts your post-surgery recovery, helping you get back on your feet faster and with greater confidence. We can address any questions or concerns you may have leading up to the surgery.

Timeline: Ideally begins 6-8 weeks prior to surgery.

Goals:

- Strengthen muscles around the knee

- Improve joint mobility

- Enhance balance and proprioception

- Educate on post-operative exercises

Key Interventions at Praxis:

- Reformer Pilates: Our modified prehab programs integrate Pilates to build core stability and lower limb strength. It’s a safe, adaptable way to enhance neuromuscular control before surgery (Levine et al., 2009).

- Balance Training: Proven to improve post-surgical function when combined with strength training [(Domínguez-Navarro et al., 2020)].

- Education: We prepare you with strategies to navigate the early post-op period, including mobility aids and pain management.

Expert Manual Therapy: Enhances joint mobility, reduces pre-surgical stiffness, and prepares surrounding tissues for optimal post-surgery performance.

Early Post-Op Phase (0-6 weeks)

Immediately following surgery, your primary goals will be managing pain, reducing swelling, and restoring basic mobility.

Many assume recovery only begins once the surgical pain fades—but getting moving early is critical. Guided physiotherapy helps you regain mobility safely, reduce complications, and build confidence from the very start.

Expect:

- Supervised sessions with focus on safe movement and circulation

- Gentle range-of-motion and isometric exercises

- Gait retraining using assistive devices

Evidence-based benefit: Early mobilisation and physiotherapy within days of surgery improve short-term outcomes (Isaac et al., 2005).

Mid to Late Post-Op Phase (6 weeks – 6 months)

At this stage, the intensity of therapy increases to target long-term function. Don’t settle for “good enough” recovery. This phase is where you rebuild your strength, stability, and full mobility—setting the stage for lasting function and confidence in your new joint.

Our Therapeutic Arsenal Includes:

- Blood Flow Restriction (BFR) Training: Using pneumatic cuffs, we simulate high-load training effects using light resistance. Safe and effective for improving strength post-TKR (Piva et al., 2019).

- Functional Strength & Balance Training: Tailored to your activity goals.

- Reformer Pilates: Reactivated in this phase to support low-impact, whole-body conditioning.

- Access to On-Site Gym Facilities: Ensures continuity and transition from rehab to independent exercise.

Patients receiving a combination of manual therapy and exercise had better functional outcomes than those receiving exercise alone (Karaborklu Argut et al., 2021), a practice we fully embrace at Praxis.

Clinical Expertise You Can Trust

Praxis Physiotherapy works in close collaboration with orthopaedic knee surgeon Dr. Kelly Macgroarty, ensuring a seamless continuum of care. However, we welcome referrals from any orthopaedic surgeon.

You’re not alone in this process. Our experienced team is with you every step of the way—offering expert care, tailored planning, and hands-on support backed by evidence and close collaboration with your surgical team

Our clinicians are highly skilled in post-TKR rehabilitation and stay up-to-date with the latest evidence-based interventions.

What Does the Research Say?

Recent studies underscore the critical value of physiotherapy before and after knee replacement surgery. Prehabilitation, including strength and balance training, has been shown to improve early recovery outcomes [(Domínguez-Navarro et al., 2020)]. Combining manual therapy with exercise yields superior functional gains compared to exercise alone [(Karaborklu Argut et al., 2021), (Abbott et al., 2013)]. Blood Flow Restriction (BFR) training and Pilates have emerged as safe, effective adjuncts to conventional rehabilitation protocols [(Levine et al., 2009), (Piva et al., 2019)]. While short-term improvements in pain and mobility are well-documented, the long-term benefits of physiotherapy interventions vary across studies, highlighting the importance of personalized care and follow-up [(Artz et al., 2015), (Fatoye et al., 2021)].

What Makes Praxis Different?

- Prehab programs starting 6+ weeks before surgery

- Use of advanced modalities: BFR cuffs, Reformer Pilates

- Access to gyms within our clinics

- Close collaboration with top orthopaedic surgeons

- One-on-one care tailored to your surgical timeline and goals

Ready to Begin Your Journey?

Total knee replacement doesn’t have to mean months of struggle and guesswork. With the right physiotherapy strategy—starting before your surgery—you can dramatically improve your mobility, reduce pain, and return faster to the activities you love. Reach out to Praxis Physiotherapy today to schedule your pre-operative assessment or post-surgical consultation. Let us guide your recovery with confidence, care, and clinical expertise.

Until next time, Praxis What You Preach…

📍 Clinics in Teneriffe, Buranda, and Carseldine

💪 Trusted by athletes. Backed by evidence. Here for everyone.

References

- Artz, N. et al. (2015). Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders.

- Domínguez-Navarro, F. et al. (2020). Preoperative strengthening and balance training. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy.

- Fatoye, F. et al. (2021). Clinical and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery.

- Karaborklu Argut, S. et al. (2021). Exercise and manual therapy vs exercise alone. PM&R.

- Levine, B. et al. (2009). Pilates for rehabilitation after total joint arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research.

- Piva, S. et al. (2019). Later-stage exercise vs usual care. JAMA Network Open.

Visit Us

CARSELDINE CLUB COOPS

751 Beams Road

Carseldine QLD 4034

TENERIFFE

91 Commercial Road

Teneriffe QLD 4005

WOOLLOONGABBA

Shop LE201, Level 2

Centro Buranda Shopping Centre

Cnr Ipswich Rd & Cornwall Street

Woolloongabba QLD 4120

Copyright 2025 Praxis Physiotherapy. All Rights Reserved.