The role for neural mobilisation?

Current non-surgical management involves rest, pain control and resistance training[4]. Though not explored within the literature, neural mobilization may have an important role in patients with persistent symptoms, such as Grade 1 moderate to severe, and more recurrent neuropraxias. Though not assessed in this specific population, there is evidence for neural tissue management being superior to minimal intervention for pain relief and reduction of disability in nerve related chronic musculoskeletal pain.[8] It is biologically plausible that recurrent neuropraxias may respond in a similar way, utilising neural mobilisation (tensioning or sliding) and mobilisation of surrounding structures.

Management of persistent Grade 1 injuries may differ slightly, specifically if the suspected mechanism of injury was through traction rather than compression. The nerve structures may have a heightened sensitivity to tensioning based techniques due to the similar mechanism of injury and may respond better acutely to sliding techniques which limit the strain on the nerve and focus on excursion. Tensioning techniques may be important in the sub-acute phase by loading the patient’s nervous system (i.e. increased strain) in preparation for return to function (i.e. tackling with acute traction on the brachial plexus).

In summary, perhaps we shouldn’t be as dismissive of “stingers”, particularly if they are recurrent for you! If you have any questions or would like to see one of our physios regarding your injury, feel free to contact us on (07) 3102 3337 or book online on our website

Till next time, Praxis what you Preach

Team Praxis

Prevent | Prepare | Perform

REFERENCES:

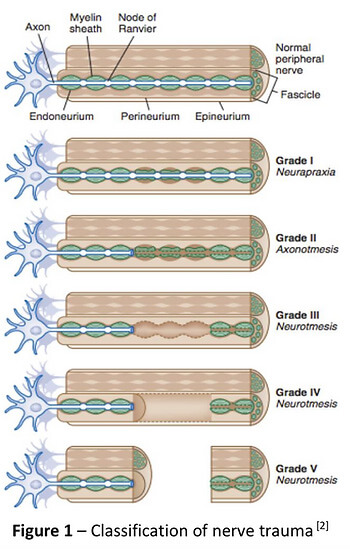

Menorca, R.M.G., T.S. Fussell, and J.C. Elfar, Nerve physiology: mechanisms of injury and recovery. Hand clinics, 2013. 29(3): p. 317-330.

Tsao B, B.N., Bethoux F, Murray B, Trauma of the Nervous System, Peripheral Nerve Trauma. 6th ed. In: Daroff: Bradley’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 2012.

Sunderland, S., A classification of peripheral nerve injuries producing loss of function. Brain, 1951. 74(4): p. 491-516.

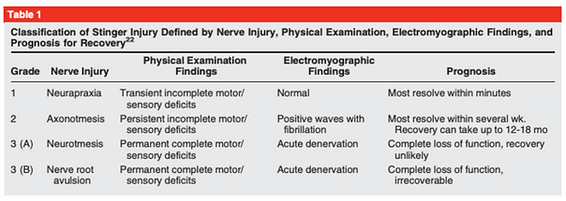

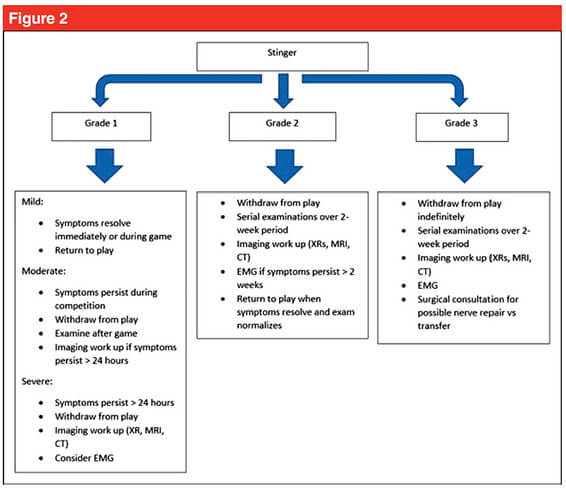

Ahearn, B.M., H.M. Starr, and J.G. Seiler, Traumatic Brachial Plexopathy in Athletes: Current Concepts for Diagnosis and Management of Stingers. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2019.

Feinberg, J.H., Burners and stingers. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am, 2000. 11(4): p. 771-84.

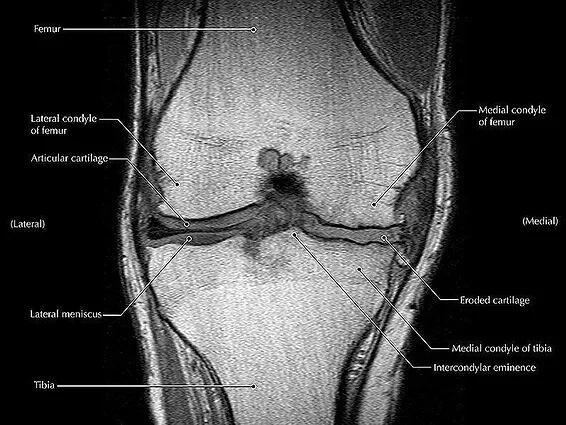

Presciutti, S.M., et al., Mean subaxial space available for the cord index as a novel method of measuring cervical spine geometry to predict the chronic stinger syndrome in American football players. J Neurosurg Spine, 2009. 11(3): p. 264-71.

Aldridge, J.W., et al., Nerve entrapment in athletes. Clin Sports Med, 2001. 20(1): p. 95-122.

Su, Y. and E.C. Lim, Does Evidence Support the Use of Neural Tissue Management to Reduce Pain and Disability in Nerve-related Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain?: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Clin J Pain, 2016. 32(11): p. 991-1004.