Navigating Knee Osteoarthritis: A Physio-Centric Pathway to Strength and Mobility Before Surgery

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common causes of chronic pain and mobility restriction in Australians over 45. Whether you’re a weekend warrior, an active grandparent, or someone just trying to keep up with the daily demands of life, OA can slowly erode your confidence in movement — long before X-rays show the full extent of joint degeneration.

At Praxis Physiotherapy, we take a forward-thinking, collaborative approach to managing knee OA. Working closely with renowned orthopaedic knee surgeon Dr. Kelly Macgroarty and drawing from our extensive experience with high-performance athletes and everyday patients alike, we believe the journey toward better knees starts well before surgery — and, for many, might even avoid or delay it altogether.

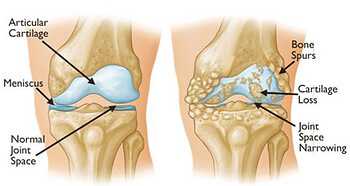

What is Knee Osteoarthritis?

Knee OA is a progressive condition involving the breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone, typically leading to:

Pain during or after activity

Morning stiffness or stiffness after rest

Swelling and inflammation

Loss of flexibility and range of motion

Difficulty with stairs, kneeling, or prolonged standing

Radiographic OA becomes more common with age, but symptoms often precede visible changes on X-ray. Up to 30% of people over 65 show radiographic OA, yet many remain functionally capable — highlighting the importance of early, movement-based interventions (Naja et al., 2021).

Why a Physio-Led Model Before Knee Replacement?

Surgery is not the first or only option. A large systematic review of 19 randomized controlled trials found that non-surgical interventions such as physiotherapy, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and structured exercise were associated with meaningful improvements in pain and function over 12 months (Naja et al., 2021). Physiotherapy, in particular, is consistently supported by international guidelines as a first-line treatment (Fransen et al., 2015; Bennell et al., 2014).

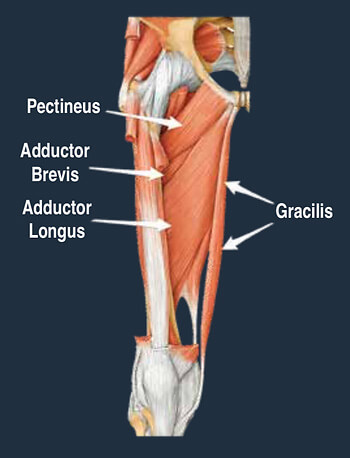

Traditionally, knee OA rehab has emphasised quadriceps strengthening — and for good reason, as quadriceps weakness is strongly linked to OA-related pain and disability. However, more recent research suggests that focusing exclusively on the quadriceps may be too narrow. Programs that include hip (gluteal), hamstring, and calf muscle strengthening are now shown to be superior in improving functional outcomes, especially for activities like walking, stair climbing, and maintaining balance (Bennell et al., 2014). This broader approach addresses the full kinetic chain around the knee, optimises joint load distribution, and better supports long-term movement efficiency.

At Praxis, our physios:

Assess gait, strength, joint mobility, and function

Design individualised exercise programs targeting quadriceps, glutes, and calf strength

Implement manual therapy techniques to restore joint mobility

Provide pain education, load management advice, and real-world strategies

Monitor progress and adjust programs over time

This proactive approach not only builds resilience in the knee but also prepares the joint and surrounding muscles should surgery eventually be required.

Booster Sessions: Keeping Gains, Lowering Costs

An often-overlooked strategy is the use of booster physiotherapy sessions — structured follow-ups after an initial rehab program. Research by Bove et al. (2018) showed that exercise programs with booster sessions at 3, 6, and 12 months were not only more clinically effective but also more cost-effective over a two-year period compared to standard physiotherapy care.

At Praxis, we now embed these booster sessions into long-term OA management. They help patients:

Maintain strength and conditioning gains

Stay accountable with home programs

Troubleshoot new symptoms early

Reduce future health care costs and medication reliance

What About Injections and Other Adjuncts?

We often collaborate with GPs and orthopaedic specialists to incorporate adjunct treatments where the evidence supports it:

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections showed significant long-term benefit for pain and function, with improvements of ~20 points on the WOMAC index. PRP ranked just behind stem cells as the most effective non-surgical treatment in a large 2021 network meta-analysis (Naja et al., 2021).

Hyaluronic acid (HA) injections have shown mixed results. A review of overlapping meta-analyses concluded that HA is likely safe and modestly effective, especially in early-stage OA, although guideline recommendations remain inconsistent (Xing et al., 2016).

Ultimately, our philosophy is to build strong knees first, and complement physiotherapy with interventions like PRP or HA only when clinically indicated and appropriately timed.

Surgical Collaboration

In more advanced cases, where conservative management fails, we work closely with Dr. Kelly Macgroarty, one of Queensland’s leading knee surgeons. Our relationship allows:

Streamlined triage for surgical consultation

Shared prehabilitation planning to improve surgical outcomes

Integrated post-operative rehab, using in-clinic gym equipment and reformer Pilates to accelerate return to function

This continuity ensures you’re never left navigating knee OA alone — whether your journey stays entirely within physio care or progresses to surgical management.

Why Praxis Physiotherapy?

At Praxis, we’ve built our care model around best-practice guidelines, decades of elite sport and private practice experience, and a shared goal of keeping our patients active, independent, and thriving.

Our Teneriffe, Carseldine and Buranda clinics offer:

In-clinic rehab gyms

Reformer Pilates for joint-friendly loading

Real-time strength testing technology

Physios with elite sports and post-surgical rehab experience

Take the First Step

If you or someone you love has been told you’re “heading for a knee replacement,” don’t wait. There is so much we can do to reduce pain, improve function, and build confidence in your knees — surgery or not.

Book an appointment today at one of our Brisbane clinics and start your journey to stronger, more resilient knees.

Interested in ACL specific rehab? Check our guide on return to sport after ACL injury

Until next time, Praxis What You Preach!

📍 Clinics in Teneriffe, Buranda, and Carseldine

💪 Trusted by athletes. Backed by evidence. Here for everyone.

References

Bove, A. M., Smith, K. J., Bise, C. G., et al. (2018). Exercise, manual therapy, and booster sessions in knee osteoarthritis: cost-effectiveness analysis from a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Physical Therapy, 98(1), 16–27.

Fransen, M., McConnell, S., Harmer, A. R., Van der Esch, M., Simic, M., & Bennell, K. L. (2015). Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(24), 1554–1557.

Bennell, K. L., Dobson, F., & Hinman, R. S. (2014). Exercise in osteoarthritis: moving from prescription to adherence. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 28(1), 93–117.

Naja, M., Fernandez De Grado, G., Favreau, H., et al. (2021). Comparative effectiveness of non-surgical interventions in the treatment of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine, 100(49),

Xing, D., Wang, B., Liu, Q., et al. (2016). Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treating knee osteoarthritis: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Scientific Reports, 6, 32790.