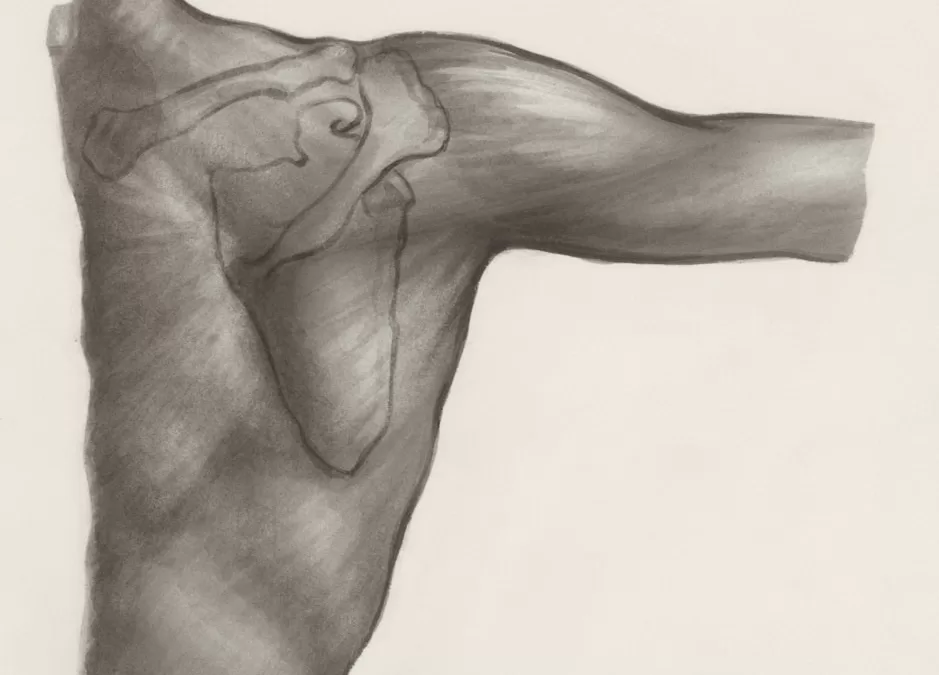

Rotator Cuff Repair: A Physiotherapy Guide on Recovery and Rehabilitation

What to Expect from Rotator Cuff Repair: A Physiotherapy Perspective on Recovery and Rehabilitation

Rotator cuff repair surgery is a common and highly effective intervention for individuals suffering from persistent shoulder pain, weakness, or dysfunction due to a torn rotator cuff. Many patients turn to Google with phrases like “rotator cuff surgery recovery timeline,” “shoulder rehab exercises,” or “physiotherapy after shoulder surgery” when looking for answers about what comes next (that may have brought you here!).

While surgical techniques have advanced significantly, the rehabilitation process that follows is equally important in determining a successful outcome. In this Praxis What You Preach blog, we outline what patients can expect from physiotherapy after rotator cuff repair, based on current evidence, clinical best practice and our years of experience dealing with post operative patients.

Phase 1: Protection and Pain Management (Weeks 0–6)

The early stage of rehabilitation focuses on protecting the surgical repair, minimising pain, and reducing inflammation. Patients are typically placed in a shoulder immobiliser or sling for 4–6 weeks to allow early tendon-to-bone healing (Sgroi & Cilenti, 2018; Nikolaidou et al., 2017).

- Passive Range of Motion (PROM) may begin within this phase under the supervision of a physiotherapist to prevent stiffness while avoiding strain on the healing tendon (Conti et al., 2009).

- Key goals include:

- Pain control (using ice, medication, or electrotherapy)

- Preventing stiffness through gentle PROM in safe planes

- Maintaining mobility of the elbow, wrist, and hand

“Excessive immobilisation can contribute to shoulder stiffness and muscle atrophy, yet too much movement too soon may compromise tendon healing” (Littlewood et al., 2015).

Phase 2: Controlled Mobilisation (Weeks 7–11)

Once the tendon is more securely integrated with bone, the sling is discontinued and patients begin active-assisted and then active range of motion (AAROM → AROM).

- Exercises now include:

- Assisted shoulder flexion and external rotation

- Scapular control and retraction exercises

- Isometric strengthening for deltoid and scapular stabilisers

This phase is critical to restoring functional movement without overloading the healing tendon. A slow and structured progression is essential. According to Bandara et al. (2021), protocols that are milestone-based (rather than time-based alone) yield better individualised outcomes.

“Criteria to progress should include pain-free PROM and AROM without compensation or shoulder shrug” (Sgroi & Cilenti, 2018).

Phase 3: Strengthening and Neuromuscular Control (Weeks 12+)

At approximately 12 weeks, patients typically progress to resisted exercises that begin to strengthen the repaired rotator cuff and surrounding musculature. At this stage:

- Isotonic rotator cuff and scapular muscle training begins

- Progressive resistance exercises (e.g. banded ER/IR, rows)

- Incorporation of proprioception and dynamic control (e.g. rhythmic stabilisation, closed-chain activities)

The focus shifts from range of motion to building load tolerance and functional strength. Exercise selection considers tendon healing biology, which shows more mature tendon-to-bone healing around the 12–16 week mark (Nikolaidou et al., 2017; Conti et al., 2009).

“Initiation of functional loading early in the rehabilitation programme does not adversely affect clinical outcome, provided it is gradual and well-monitored” (Littlewood et al., 2015).

Phase 4: Return to Activity and Sport-Specific Rehabilitation (Month 4+)

From four months onwards, many patients begin returning to higher-level tasks depending on their goals:

- Overhead activities for daily life or sport

- Plyometric and ballistic loading for athletes

- Work conditioning or manual labour readiness

At Praxis Physiotherapy, we tailor this phase to your individual goals—whether that’s lifting your toddler, swinging a golf club, or returning to competitive sport.

Some protocols extend formal physiotherapy through months 6–12 for more complex tears or high-functioning individuals.

Communication and Individualisation are Key

Every patient recovers at a different rate depending on:

- Size and chronicity of the tear

- Surgical technique

- Pre-existing stiffness or atrophy

- Adherence to rehabilitation and exercise

Close collaboration between surgeon, physiotherapist, and patient is essential for long-term success (Sgroi & Cilenti, 2018; Nikolaidou et al., 2017).

“There is strong evidence that early initiation of rehabilitation does not adversely affect clinical outcomes, but should always be individualised” (Littlewood et al., 2015; Bandara et al., 2021).

Final Thoughts

Rotator cuff repair is only the beginning of the journey. At Praxis Physiotherapy, we provide evidence-based, goal-oriented care from day one post-op through to full return to work, life, and sport.

If you’re preparing for rotator cuff surgery or are currently in recovery, book an appointment at one of our Brisbane locations to begin a structured and personalised rehabilitation program. Begin your recovery the right way.

Until next time, Praxis What You Preach

📍 Clinics in Teneriffe, Buranda, and Carseldine

💪 Trusted by athletes. Backed by evidence. Here for everyone.

The Athletic Shoulder: Why Sport-Specific Rehab Matters

The Athletic Shoulder: Why Sport-Specific Rehab Matters