Knee Osteoarthritis: Is ‘Bone on Bone’ a painful life sentence?

- Knee Osteoarthritis is a common ailment responsible for pain, loss of function and reduced quality of life

- Rates of knee OA are set to increase

- Whilst there is no cure, exercise therapy under the guidance of a physiotherapist is considered a front line treatment to help reduce the severity of symptoms

- There are options before a knee replacement

Do your knees go crackle and pop? Pain with walking, stairs or getting out of a chair? Stiffness and pain first thing in the morning or after a long car ride? These are signs that you may be living with the early or even advanced symptoms of knee osteoarthritis (OA). Don’t fear though – there is plenty that can be done immediately.

What is “OA”?

Osteoarthritis (OA) is an increasingly prevalent source of musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction. OA is a disease of the joint – including cartilage, bone, capsule and other associated tissues. This disease process can cause chronic pain, reduced physical function and diminished quality of life. The ageing population and increased global prevalence of obesity are anticipated to dramatically increase the impacts of knee OA and its associated impairments [1]. Although osteoarthritis can affect any joint, OA is knee is one of the most common complaints.

Presentation

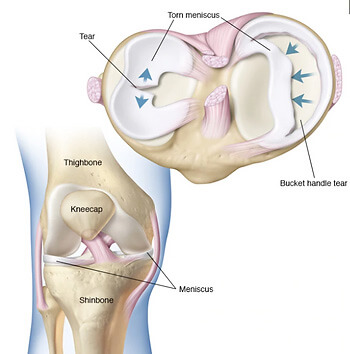

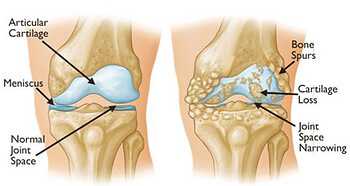

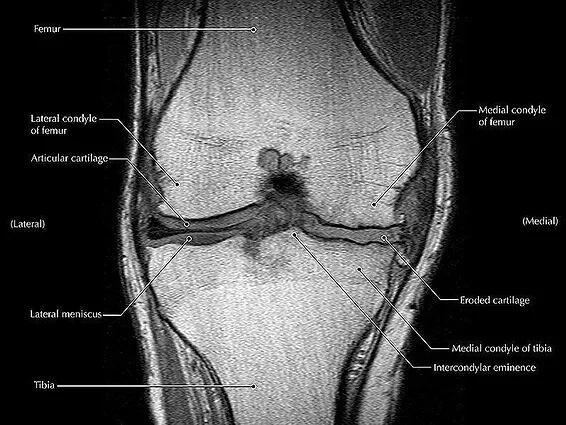

It most commonly presents in people over the age of 50, and is often described as being painful, stiff and occasionally swollen. In terms of a tissue level, knee OA describes the gradual deterioration of the supportive cartilage within the knee joint. As the cartilage wears away with time, the protective joint space between the bones decreases. With a reduced cartilage lining to protect and support the spacing of the knee joint, the Femur and Tibia (knee bones) are increasingly less likely to dissipate forces through the joint . With time, it should be expected that bone spurs (osteophytes) may form in and around the joint as the bones react to repetitive contact with each other.

Management

The management of knee OA largely consists of exercises addressing strength, range of motion, quality of movement, emphasizing joint control, pain reduction and weight management.

Strength Training

Strength training should be the cornerstone of addressing knee OA, particularly the early signs. Strengthening the muscles around the knee joint, such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes provide better support to the knee, reducing stress on the joint and helping to alleviate pain and discomfort. Movement associated with exercise has an added benefit – It increases joint lubrication. Loading of the joint stimulates the production and distribution of synovial fluid within the joint. This fluid acts as a lubricant, reducing friction and providing cushioning to the joint surfaces. Improved lubrication can help alleviate pain during movement.

Range of motion

Knee osteoarthritis often leads to stiffness and limited range of motion in the joint. Physiotherapy can include specific exercises, manual therapy and stretches to improve joint flexibility, helping to restore a more normal range of motion and enhancing mobility. The greater the restoration of range, the better the knee feels.

Pain reduction

Both strength training and physiotherapy can help reduce pain associated with knee OA. As mentioned, stronger muscles provide better support to the joint, relieving pressure and reducing pain during movement. Physiotherapy may provide education of aggravating and easing factors (eg. hot / cold packs, hydrotherapy) as well as liaise with your GP for adequate analgesic medications.

Lifestyle modifications

Adopting a healthy lifestyle can play a pivotal role in managing knee osteoarthritis. Maintaining a healthy weight reduces the stress on the knee joints. Regular low-impact exercises such as swimming, cycling and reformer pilates help improve strength, flexibility, and overall joint health. A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can promote weight loss and provide essential nutrients for joint health. Quitting smoking and minimizing alcohol consumption are also beneficial.

Improved weight management

Regular exercise can assist in weight management, which is crucial for individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Excess weight puts additional strain on the knee joint, contributing to pain and progression of the condition. By maintaining a healthy weight, exercise helps to reduce the load on the joint and alleviate pain.

Surgical Interventions

When conservative measures fail to provide relief, surgical interventions may be necessary. Procedures such as arthroscopy, osteotomy, and joint replacement surgery can help repair damaged tissues, realign the joint, or replace the damaged joint with a prosthetic. These surgeries can significantly improve mobility and reduce pain, allowing individuals to resume their daily activities. Physiotherapy can aid in preparing you for the surgery, as well as rebuild your “new” knee after a knee replacement has been completed.

In conclusion, while knee osteoarthritis can be challenging, it is not a condition that should hinder individuals from leading fulfilling lives. By implementing lifestyle modifications, exploring various treatment options, and working closely with your physiotherapist, individuals can effectively manage their symptoms, alleviate pain, and enjoy an active lifestyle with a sense of well-being. If conservative options fail, there are surgical interventions that can be investigated. If you are wanting to look after your knees, or already suffering from knee pain, chat to our knowledgeable Praxis Physios to discuss your treatment options at any stage of OA’s progression.

Until next time,

Praxis what you Preach