Strong Bones, Strong Runner: Understanding and Treating Stress Fractures

Understanding Stress Fractures in Runners: Risk, Recovery, and Prevention

Stress fractures are a frustrating reality for many runners. Characterised by small cracks or severe bone reactions due to repetitive load, these injuries can derail training for weeks or months, and in some cases, end seasons or careers. While they are most commonly associated with endurance sports like distance running, the underlying mechanisms are multifactorial and complex. This blog explores the current understanding of stress fractures in runners — including emerging research, rehabilitation strategies, and how to lower your injury risk.

What Is a Stress Fracture?

A stress fracture is a type of bone stress injury (BSI), an overuse injury caused by the accumulation of microdamage in bone tissue due to repeated loading. Unlike acute fractures that result from a single traumatic event, stress fractures occur when repetitive sub-threshold forces — like running — outpace the bone’s capacity to repair itself (Hoenig et al., 2022).

Bone is a dynamic tissue that remodels in response to stress. However, when this remodeling process cannot keep up with microdamage accumulation — due to either an increase in training load or inadequate recovery — bone strength deteriorates. This can progress from a stress reaction to a stress fracture and, if untreated, to a complete fracture (Bergman & Kaiser, 2025; Coslick et al., 2024).

Why Are Runners So Prone?

Running, by nature, imposes repeated high loads on the lower limbs. The tibia (shin bone), metatarsals, femur, and pelvis are frequent stress fracture sites in runners (Hadjispyrou et al., 2023). Several factors contribute to the elevated risk in this group:

Training Errors: Rapid increases in volume or intensity, excessive hill work, or high mileage without adequate rest periods.

Bone Geometry: Martin & Heiderscheit (2023) found associations between proximal femur geometry and increased stress fracture risk, suggesting that individual anatomical differences can affect how load is distributed through the skeleton.

Energy Deficiency: Low energy availability, often associated with disordered eating or high training demands, can impair bone remodeling and increase injury risk — particularly in female athletes.

Surface and Footwear: Hard surfaces, old or inappropriate shoes, and poor running biomechanics can all contribute to abnormal load distribution and localized bone stress.

High-Risk vs Low-Risk Locations

Not all stress fractures are created equal. According to Coslick et al. (2024), stress fractures are categorized based on location and associated risk of complications:

Low-risk sites (e.g., posterior tibia, fibula, second metatarsal shaft) typically heal well with conservative treatment.

High-risk sites (e.g., anterior tibia, navicular, femoral neck, and sacrum) are more likely to progress to non-union or full fracture and may require surgical management.

A nuanced understanding of the fracture location helps guide both treatment duration and rehabilitation intensity.

The Cumulative Risk Concept

Traditional models have viewed stress fractures as the result of isolated risk factors. However, Hamstra-Wright et al. (2021) propose a more integrated concept: the cumulative risk profile. This model acknowledges that risk factors — like energy deficiency, training load spikes, biomechanics, menstrual history, and previous BSIs — rarely occur in isolation.

In this framework, stress fractures occur when the athlete’s “load capacity” is exceeded by their “training load.” What’s striking is that two runners could follow the same training program but respond very differently based on their individual capacity, bone density, and recovery habits.

Clinically, this means runners must be assessed holistically. It also underscores the importance of individualized training plans, particularly during return-to-run phases.

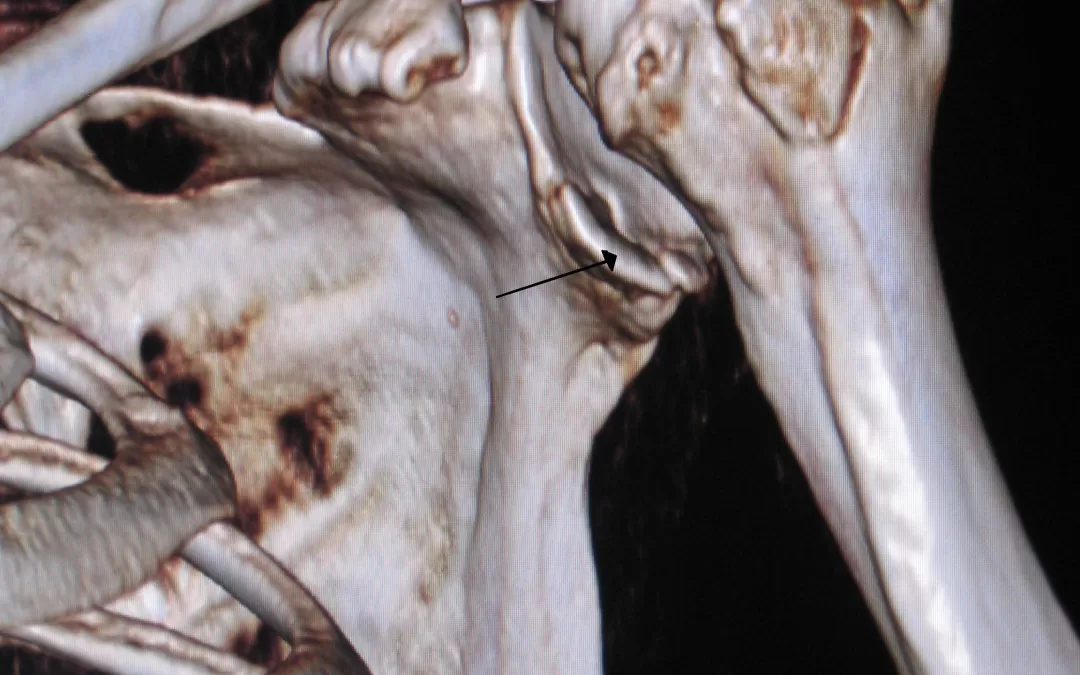

Diagnosis and Imaging

Early symptoms of a stress fracture include localized pain that worsens with activity and settles with rest. As the injury progresses, pain can persist with walking or even at rest.

Unfortunately, standard X-rays often miss early bone stress injuries. MRI is the gold standard, able to detect bone marrow edema (early stress reaction) before a fracture line develops (Coslick et al., 2024; Bergman & Kaiser, 2025). Bone scans and CT can also be used in specific cases.

Rehabilitation and Return to Running

The cornerstone of stress fracture management is load reduction, typically involving rest from impact activities for 4–8 weeks depending on the site and severity. During this time, runners can usually continue cross-training (e.g., cycling, swimming) to maintain cardiovascular fitness.

A gradual return-to-run program should be guided by symptom response, starting with walk–run intervals and progressing to continuous running. Strength and conditioning plays a vital role in both rehabilitation and prevention — building muscular resilience to offload bony structures. Calf, hip, and core-focused strength work can significantly reduce recurrence risk and should form part of a comprehensive return-to-run strategy. (You can learn more about how we use strength and conditioning at Praxis Physiotherapy to support our runners here)

Coslick et al. (2024) emphasises the value of a multidisciplinary approach involving physiotherapists, sports physicians, dietitians, and coaches.

Preventing Stress Fractures: What Runners Can Do

While not all BSIs are preventable, runners can reduce their risk by addressing modifiable factors:

Progress training gradually: Avoid spikes in weekly mileage (>10% per week) and ensure at least one rest day.

Fuel adequately: Runners with low energy availability are at significantly increased risk, particularly females with menstrual disturbances.

Build strength: Muscle fatigue reduces shock absorption. Strengthening the calves, glutes, and trunk can reduce bone loading.

Check your shoes and form: Replace runners every 500–800 km and consider a running gait assessment, especially if you have a history of injury.

Listen to your body: Early symptoms like persistent aching, pinpoint bony pain, or pain that lingers after a run shouldn’t be ignored.

The Bottom Line

Stress fractures in runners are complex, multifactorial injuries that require a careful balance of training load, nutrition, and recovery. While new imaging and biomechanics research has enhanced our ability to diagnose and understand them, the best approach remains holistic — considering both the runner’s physiology and their environment.

At Praxis Physiotherapy, we manage bone stress injuries in athletes of all levels. Whether you’re dealing with your first tibial stress reaction or a sacral stress fracture during marathon prep, we can help guide your recovery and reduce your future risk. Book with us today!

If you’re interested in how stress fractures affect other athletes — like fast bowlers in cricket — read more our blog on lumbar spine stress fractures here.

Until next time, Praxis what you Preach

📍 Clinics in Teneriffe, Buranda, and Carseldine

💪 Trusted by athletes. Backed by evidence. Here for every body.

References

Bergman, R., & Kaiser, K. (2025). Stress Reaction and Fractures. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from

Coslick, A. M., Lestersmith, D., Chiang, C. C., Scura, D., Wilckens, J. H., & Emam, M. (2024). Lower extremity bone stress injuries in athletes: An update on current guidelines. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports, 12(1), 39–49.

Hamstra-Wright, K. L., Huxel Bliven, K. C., & Napier, C. (2021). Training load capacity, cumulative risk, and bone stress injuries: A narrative review of a holistic approach. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 665683.

Hadjispyrou, S., Hadjimichael, A. C., Kaspiris, A., Leptos, P., & Georgoulis, J. D. (2023). Treatment and rehabilitation approaches for stress fractures in long-distance runners: A literature review. Cureus, 15(11), e49397.

Hoenig, T., Ackerman, K. E., Beck, B. R., Bouxsein, M. L., Burr, D. B., Hollander, K., Popp, K. L., Rolvien, T., Tenforde, A. S., & Warden, S. J. (2022). Bone stress injuries. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 8, 26.

Martin, J. A., & Heiderscheit, B. C. (2023). A hierarchical clustering approach for examining the relationship between pelvis–proximal femur geometry and bone stress injury in runners. Journal of Biomechanics, 160, 111782.

A Multimodal Approach

A Multimodal Approach